Farewell to a cricket icon

We had hoped and prayed for the best but we feared the worst

Tony Cozier

18-Jul-2010

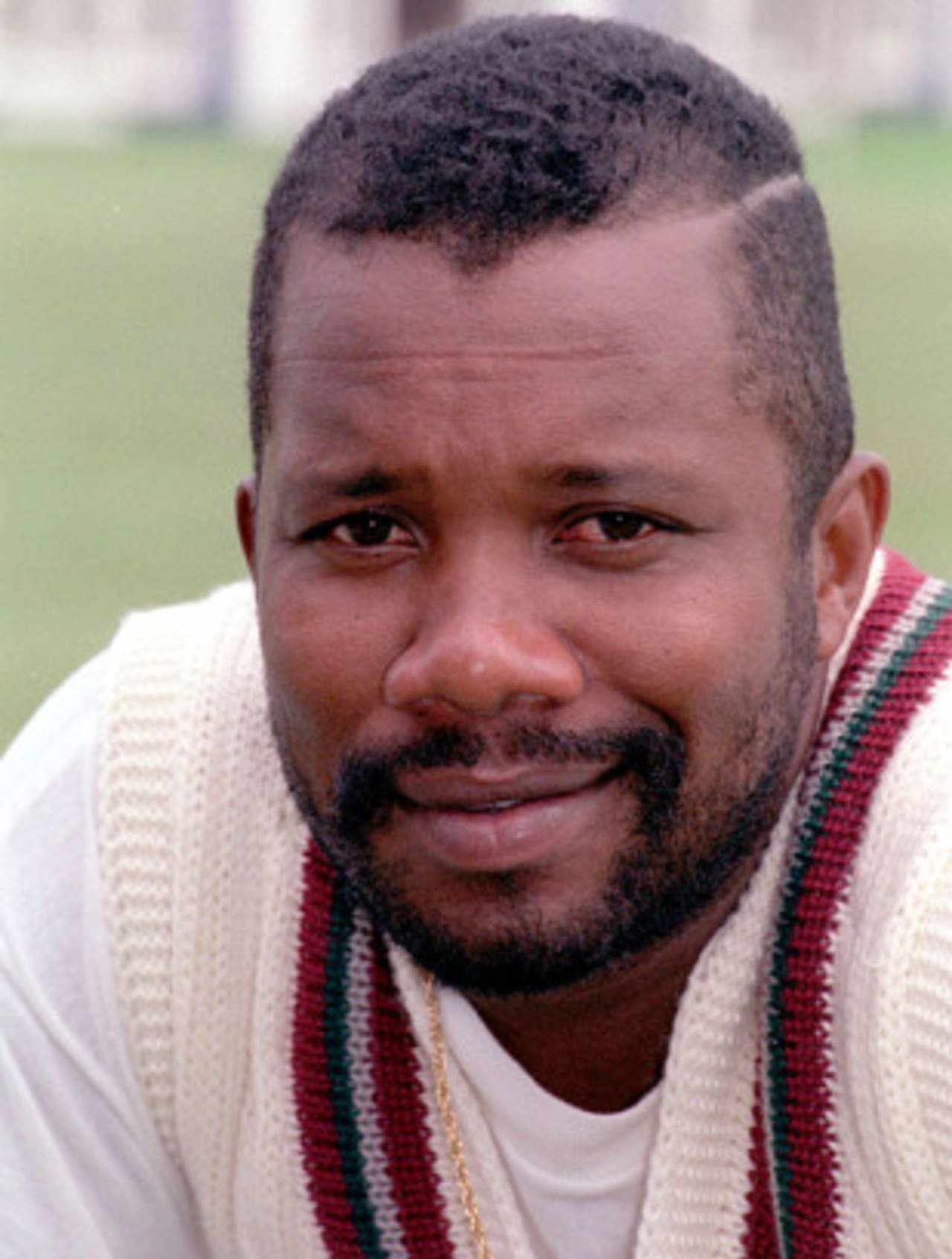

Malcolm Marshall: a revered icon • PA Photos

We had hoped and prayed for the best but we feared the worst.

We knew that if anyone could overcome the dreaded illness that struck him down last May, it would have been Malcolm Marshall with his positive attitude to life. We also knew, deep down, that the tardy detection of the cancerous tumor that had to be surgically removed from his colon left him with only the slimmest chance of survival.

In the end, we had to accept it was inevitable, but that has not softened the blow any for crickets global community which has lost not only one of the greatest exponents of the art of fast bowling but one of its most admired and respected members at a shockingly young age.

To have heard Michael Holding, that most noble of men, initially choked with emotion when asked, on the radio commentary of the Red Stripe Bowl semi-final Friday, for his thoughts on the passing of his friend and colleague was to understand the esteem in which Malcolm Marshall was held by his peers.

The grief is sharpest in this island most of all, of course. This little rock was where he was born, bred and learned the game that he came to love and perfect with such passion. It was where he was a revered cricket icon among the many. But hearts will be heavy as well in England where he was an adopted and adored son in the country of Hampshire to whom he gave 14 of his best years as player and coach.

And there will be a legion of white people in South Africa who today are mourning the passing of a small, but amazing, black man from a tiny island on the other side of the world who came and taught them

not only how to bowl but how to appreciate the simple truth that we are all equal in the eyes of God.

His passing equates with the death at a similar age 32 years ago of another legendary West Indian cricketer, Sir Frank Worrell. Both had given so much as players and then in positions of influence, Worrell as captain, Marshall as coach. Both had so much more to give when cancer took them away.

Our cricket is currently passing through difficult times. Our young players seem to have lost their way and need the guidance more than ever of those who understand the need for discipline, commitment,

pride and diligence. No one more acutely appreciated such values than Marshall.

After he regained his composure Friday, Holding told of his belated discovery that his fast bowling partner - at 5ft 10in and 175 pounds a mere middleweight to the heavyweights at the other end - boosted his critical strength by jogging with sandbags on his legs.

Forced into premature retirement after he was dumped from the West Indies team during the World Cup in 1992 on the shamefully false pretence that he was injured, Marshall noted: Everything seems to be

going down the drain. There is no respect, no manners.

It seemed to some at the time a typically bitter blast from a departing player but it proved impossible to refloat them since. As coach, Marshall had only three short and turbulent years to help in the revival. He was often driven to desperation by the internal problems that led to the drubbings inflicted by Pakistan in 1997 and South Africa last season.

To have heard Michael Holding, initially choked with emotion when asked, on the radio commentary, for his thoughts on the passing of his friend and colleague was to understand the esteem in which Malcolm Marshall was held by his peers

But he was encouraged by the recent revival against Australia, the world champions, and by the emergence of exciting new players like Ricardo Powell, Pedro Collins, Corey Collymore and Wavell Hinds. He still held out great hope for Brian Lara as captain and for Merv Dillon and Nixon McLean. He was beginning to see the first light of a new dawn when his mission was cut short.

Everyone will have his or her own fond memories of Malcolm Marshall. Perhaps the most popular image will be of the one-armed bandit in Leeds in 1984, broken left thumb in plaster, flailing bat in right hand as he defied doctors orders to come in last simply to shepherd team-mate Larry Gomes to a deserving hundred. He then reappeared, changed his white plaster to something nearer to his skin colour at the insistence of England's batsmen and scattered them to defeat with irresistible bowling that brought him seven

wickets.

A few of my recollections are less obvious. One, I feel, would please him immensely for he placed great store on his batting. It was of his flourishing flick through midwicket that carried the hallmark of his favourite player, Seymour Nurse. His greatest disappointment might well have been that he did not score a Test

hundred, as he was quite capable of doing.

Another is of his winning for Barbados a Shell Shield match in Grenada with three wickets of legspin - yes, legspin - when the Windwards seemed likely to hold out. He really could do anything with the ball.

My final sight of Malcolm Marshall was, at one and the same time, the happiest and the saddest. It was at the Priory Hospital in Birmingham, England, in May, a couple of days after his operation when, with his beloved Connie by his side, he was joking and skylarking, as he always would, with his old pal,

Desmond Haynes, when Gordon Brooks, my son, Craig, and I paid a visit. He was in such an upbeat mood that we left him buoyed with optimism. His maker had other designs. He has decided to call him away, leaving us mere mortals to celebrate a life, short as it was, that was of such significance.